All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. However if you think that the situations I describe could never happen. then you could be right – or maybe……….

What is truth? Memory isn’t truth. Memory is edited almost as soon as the moment passes, then filtered through time and self-importance. A layer of ‘now’ is always imposed onto ‘then,’ and these stories are from so far back in my ‘then’ that all that’s left are the bits that stick up from the rest like an old stump in a bog, or perhaps an old bicycle frame in a river.

A bicycle frame in a river . . .

This is the story of The Floating Dutchman. Some people go missing because they want to, others go missing in their own heads, poor sods, and then there are those who go missing simply because they got lost. The Floating Dutchman was probably one of this last sort.

Some time ago, when the world was young and beer and tobacco cheap, a man was found in a river still holding on to, and a little bit entwined with, his bicycle. The river was the Colne, which meanders from somewhere soggy in Cambridgeshire, carving itself a gentle valley along the way, and eventually ending up as a wide estuary on which lurks the port of Harwich. During the course of its journey to the sea this river acts as a boundary between the counties of Essex and Suffolk.

That last bit is significant: On one side of the river, the noble Essex Police; on the other, the Suffolk Constabulary. There has always been a ‘friendly’ rivalry between these two forces, not unlike that which existed between the English and the Welsh during the middle ages. An attitude of deep suspicion, always on the lookout for underhanded dealings. I’m just telling you this so you’ll understand the dynamics of what follows. Now read on.

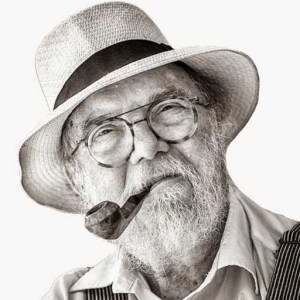

At about seven in the morning on a cold Sunday in the early Autumn, a ‘999’ call was made from a phone box on the old A604 road close by the village of Sturmer in Essex. It was passed by the gods of headquarters to the local police who were on patrol in the area. One of these was me. A lad of some thirty-plus summers, still keen and skittish from my months in the police training Stalag, fit, bearded and ripe for adventure. A virgin constable with shiny buttons and a soul untarnished by the wicked ways of the world.

Sitting by my side as I drove, and in nominal charge, was one Alf Peabody, a senior constable and sometime acting sergeant who, despite his considerable girth, scruffy uniform and foul tobacco pipe, was a damn good copper. Alf stood over six feet tall in his massive, black ammunition boots that could, and sometimes did, break down doors. He wore the medal ribbons of the Atlantic Star for service in the Second World War (as a naval rating on the Atlantic convoys) along with the nineteen thirty-nine to nineteen forty-five star which told those who knew that he was a man of that generation of steel who had lived in some of the most ‘interesting’ times of this century.

His round face was gently lined around the eyes, like a parchment on which rather too much sorrow had been written. He had a quite wicked sense of humour and was completely unabashed by any authority except that of his wife, Maude, who ruled him and their huge family with a rod of iron.

Alf knew the rule book backwards and sideways and could always find some Queen’s Regulation to hide behind when necessary, and his knowledge of by-laws, statutes and criminal law was unparalleled. He was not only a man of considerable experience in police procedure, but also a shrewd observer of the human condition. He was a font of local knowledge and had been a rural beat copper for close to twenty years. What he didn’t know about the area and its scamps, scoundrels and rotters was really not worth knowing, and his talent for finding a quiet place to hide up while he had a smoke was legendary.

So it was Alf and I in our somewhat battered Police minivan who made our way to the Colne that gentle morn. All we had been told was that a man had been seen in the water, possibly cycling but probably dead.

Sudden death in all its interesting guises is not unfamiliar to a copper in rural parts. It’s amazing just how inventive people can be in terminating their own existence, let alone someone else’s. And the countryside abounds with all manner of sharp. blunt and/or lethal objects apart from the ubiquitous shot gun. Farms themselves are inherently dangerous. And I don’t just mean the machinery which, if not treat with respect, will grab, mash or run over the unwary, but such things as silage pits, hay ricks and pig pens, which have their own winning little ways when it comes to maiming or (if you’re really unlucky) killing you outright (eventually).

But the ‘sudden’ we coppers really loathed was death by drowning, especially if it had taken place some time before the deceased was discovered. That, old darlings, is inclined to be, shall we say, ‘oozy’. Bits have a nasty way of coming off in your hands, which can put a chap right off his breakfast. A sausage was never the same for a while afterwards, I can tell you!

We found our way to the telephone box, which sat under a huge old oak tree at the entrance to a small lane where an elderly cove waived at us in a somewhat frantic fashion. He was your typical country walker of the hound, aged about sixty, with a battered flat cap on top of a somewhat florid face that was dusted with that grey stubble which denotes the occasional shaver. Small bright eyes like those of an interested shrew lurked under his bushy eyebrows. His nose indicated a man not unaccustomed to strong drink. He wore a large and somewhat stained ex-army bush jacket (the sort with several large pockets), baggy trousers tucked into Wellington boots, and carried a stout walking stick. In brief, he looked like a bit of a poacher. Alf missed none of this.

The man’s dog was a somewhat ancient Labrador who seemed immensely attracted to Alf’s crotch for some reason. Most dogs were drawn to the pocket Alf sometimes carried his ferrets in, but not this old beast.

Our poacher showed us to the scene of the crime, which was not too far away. It was approached by a narrow lane, just wide enough to take a vehicle, with trees all along one side, but only a small bank and scrubby hedge on the other where telegraph poles stuck up like javelins. This abutted a small field which was next to the wide riverbank. The lane then carried on with a bit of a lay-by just before it got to a small bridge which spanned the river. We parked our police van in this lay-by.

Walking through tall, dew-soaked grass and nettles, Alf and I came to the riverbank, which had the look of being recently scoured by flood water. The river was at it’s widest here and must have been some twenty-five to thirty feet across. It narrowed as it passed under the bridge, but the water was slow moving, dark green, and with snotty skid marks on the surface. It stank. Twigs, leaves and other flotsam slowly swirled around like spectators to the bobbing of what was unquestionably a human head.

We watched as this apparition, by the workings of the current or its own internal buoyancy, rose above the surface and revealed that it was indeed a man, and that man was, if not riding a bicycle, certainly attached to one. He seemed to be embracing the curved racing handlebars, and a weed-festooned saddle was definitely in contact with the lower half of his torso. As we watched, he went down again as if he was riding the riverbed like some ghastly two-wheeled submariner.

We asked our local guide if he knew how deep the water was and he told us there had been a lot of rain over the past week or so and the river was as full as it could be. This part, he told us, was fed by the main river as well as the Stour Brook, so there was a lot of water running into it. He used to fish here and it was renown for huge pike. Oh joy.

There was a wide sward leading to the river’s edge on the Essex side. On the Suffolk side, trees grew almost to the river bank itself, with only a narrow footpath following the line of the river. The lane continued on the Suffolk side, with trees overhanging either side in bosky profusion.

The embuggerance of it was that the poor soul on the bicycle was over ‘our’ side of the river. It would be us who had to land him, and call out the coroner’s officer and perform all the other dread rituals that have to be observed in cases like this. And it wasn’t just the thought of the time and paperwork which appalled us, but the sheer mechanics of getting him close enough to handle.

Just a little ‘aside’ at this point: One had a uniform-cleaning allowance once a year, when you took your full kit and had it dry-cleaned at the county’s expense. If in the course of your duty throughout the rest of the year your uniform became polluted by substances or smells, you needed a signed authorisation from a senior officer before you could get the garments cleaned. In our case, said senior officer was a miserable git who insisted on a full written report. It could take weeks for the paperwork to meander through the system, and in the meantime you were down to one tunic, a pair of trousers and no overcoat. So getting the clothes you stood up and saluted in more than usually mucky was not advisable.

Right, back to the riverbank.

Our trusty poacher, having shown us the place, was obviously uncomfortable with the idea of spending more time in the company of the ‘old Bill,’ and besides, we needed privacy in which to work out our strategy. So Alf asked him to go back up the lane to the junction with the main road and wait there while we called up reinforcements, who he could then show the way. Alf told him this was an important job and, after writing down his name and address, sent the bugger on his way.

Alf then lit his pipe and pondered for a while. As he pondered, the cyclist occasionally rose up and down as if on a very gentle aquatic carousel.

‘If we can just sort of nudge him over, we can report back that it’s not our problem and HQ can call up the Suffolk boys to deal with it,’ said Alf.

This worried me. Just how the bloody hell were we going to ‘nudge him over’? Also, I knew that if anyone did any ‘nudging’ it would be me, with my trousers rolled up, struggling to stay upright, standing on god knows what in the middle of a bloody wide river that could be any depth in any place.

‘I’m not going in and that’s that,’ I said.

Alf looked at me with the compassion of a wise man for an idiot, but a wise man who knew that if push literally came to shove the junior partner would be the one with soggy Y-fronts under soaking serge trousers.

‘There has to be another way!’ I pleaded.

Now in those far off days, in every police van there was a whole lot of jolly useful ‘stuff’. There was, of course, all the official paraphernalia loved by the Police Authority, plus items that were essential to rural policing, such as rabbit snares and similar. There were those ‘police slow’ signs that cause a merry chuckle as they inflict delays and hold-ups, and there were triangle signs for hazards that, by their bad design and rubbish construction, were more of a danger to the copper in erecting the sodding things than the ‘hazards’ they warned of. Then, of course, there were crow bars, leavers and other bits of serious metal used to prize open doors and vehicles. And, probably the most useful of the lot and the one most nicked from other coppers, the fire brigade and anyone else who left one lying about for redistribution, a broom.

‘Get the broom,’ said Alf.

I went to the van and got the broom, bearing the sacred object back to Alf as if it were Excalibur, and handed it to him.

Now here I admit I made a fundamental mistake, and one I would soon regret. The thing is, I do like a bit of poetry (in the long dark reaches of the night one can tuck oneself away out of reach of the sergeant and other organs of power and have a quiet read) and of course bits do tend to adhere to the brain like fluff on a boiled sweet that’s been sucked for a while and then set aside for later. Well, there was Alf holding the broom, peering into the water, and there was me just standing there like the spare one at a wedding, and it just had to be said. The words seemed to bubble up from some mysterious depth, much like our cyclist. Thus I declaimed, with just a little adjustment to make it entirely topical, the following verse:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alf and his sacred river ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

‘Oh bloody clever,’ said Alf. ‘Now get hold of this fucking broom and make yourself useful. Lean over the bank. I’ll hold onto you and you try to nudge him over.’

So, off with the tunic and, Alf holding on to my trousers at the back by my belt, his stout boots digging into the turf like the seasoned pub tug-of-war participant he was, I leaned out over the water. Its murky brown depths were full of noxious mystery. A condom floated by, indicating that romance was not dead in these parts, unlike the poor bugger on his bike. I stretched out as far as I could, trusting in Alf’s solid grasp on my belt, but the broom was still a good foot too short. So near yet so bloody far.

Alf made a merry quip about ‘what you said about me and this river,’ but eventually pulled me back on to the bank. I stood upright, grateful not just for being vertical again, but also for the relief from having the crotch of my trousers pulled into my wedding tackle in such a way as to seriously restrict the old ‘Victor Silvester’ (from Victor Silvester and His Ballroom Orchestra – old joke).

‘We need a bit of extra length,’ said Alf, peering at me with absolutely no sympathy as I tried to shake some life back into the floppy parts by putting my hands in my pockets and shaking it all about.

‘When you have finished playing pocket billiards let’s see if there’s something around here we can use.”

We scratched around on the bank and amongst the tall grass next to the field we came upon an old fence paling stuck in the hedge with a few strands of wire attached. This piece of timber was about four inches in diameter and approximately four feet long. This would do if we tied it to our trusty broom.

One of the great benefits of civilisation, dear reader, is bailing twine. It has a thousand and one uses and no police van was complete without a bloody great ball of it. Thus Alf was able to bind our broom to the wood fence post.

Now all this must have taken about half an hour and the morning was getting on and we were both worried about the arrival of onlookers and witnesses to our dastardly deeds. It would have been obvious to anyone that we were not trying to get the poor bugger to our side of the river, so things had to be done and done quickly.

Once again I was held over the murky depths of the river and this time the head of the broom was able to make contact with the bicycle. As if jousting, I aimed for the bottom of this funerary vessel and gently pushed.

Nothing happened. I pushed a bit more while Alf held on to my belt, which I was terrified was going to give way. It was only a narrow leather belt with a very indifferent buckle, after all, and the water was bloody close now, slurping underneath me, little bubbles coming to the surface disturbed by my action with the broom, which was surprisingly heavy, probably with weed (I hoped).

At last the broom head seemed to make contact with the rear wheel of the bike, which must have been the heaviest bit, and things started to move. Freed from the weeds and mud, the rear wheel rose enough for the current to take the bicycle in its grasp and slowly move it to the centre of the river. As it did so, huge bubbles erupted all around the bike and probably from within its soggy passenger as well. The smell was overpowering, which made us even more desperate to get the bloody thing over to the Suffolk side of the river; if it stank like this now, almost submerged, what would it smell like after being dragged up the river bank!

My hands were full of stick and Alf’s hands were full of me, so neither of us could do anything except try not to breath. I pushed again, this time nudging the back of the rear wheel, which thankfully propelled the bicycle forward and, in an almost swan-like glide, it bobbed and rocked flatulently across the midway point of the river. There with a noisome sigh it came to rest, well over on the Suffolk side. In fact it had settled now and the front wheel pointed towards the bank, while the rider’s head occasionally rose from the water as if peering up now and then to look for someone on the nearby footpath.

Joy unbounded was in our hearts, but danger still lurked for this intrepid duo, for through a gap in the trees on the Suffolk side we saw the flashing of a blue light. We threw the broom and paling into the undergrowth and, with the speed of men in the wrong place at the wrong time, ran back to the van, closed its doors and put on our tunics. It was too late to drive away, so we stood solemnly looking at the place in the river where a little head occasionally broke the surface like a large, weed-flecked egg.

Down the small lane opposite drove a big, shiny, white Suffolk Police car in the front seat of which sat a big, shiny, white Suffolk Police inspector. In the back seat were what we took to be two Suffolk Police constables or something similar.

The car stopped and the inspector unfolded from his crouched position behind the wheel and stood up. ’Strewth he was big! With his smart uniform, pressed trousers and the inspector’s tabs on his epaulettes gleaming like two huge dollops of bird poo, he had all the charm of a blocked drain. He also had a face like a clenched buttock. He was not a happy man. Two Neanderthals fell out of the back seat, moved to a respectful distance behind him and rested their knuckles on the ground. They said nothing.

The inspector saw us and put on his peaked cap, the white crown of which indicated to all and sundry that this was an ‘officer’ and thus to be treated with the maximum arse licking possible. We stood to attention and saluted. If there’s one thing these officer buggers like, it’s a salutation with the old right arm going up as quick as may be. Not to do so could well have earned us a ‘fizzer’ from our own dear inspector because, regardless of county, these bastards clung together like haemorrhoids, and this one looked the sort who would have reported us like a shot.

‘Oh fuck,’ murmured Alf through tight lips, ‘its Stringent Stanley. He’s a right bastard!’

Inspector Stanley acknowledged our salutes with the casual grace of a superior being and peered across the river, looking long and hard in our direction. I arranged my face to appear as innocent as a nun at an orgy, and I knew from experience that Alf could do ‘dumb insolence to a tee, especially if he was in the frame for a good bollocking.

The superior being then looked down into the river and caught sight of the dear departed, whose head bobbed slowly up and down as if in some watery way he also was paying homage to the inspector of police.

It was not lost on the inspector that this aquatic disaster was nearer to him than it was to us. It was also not lost on him that there had been some considerable disturbance in the river from the way the mud had come to the surface along with other jolly flotsam. There was definitely something ‘fishy’ about the whole scene.

At last, recognising my trusty partner, his unpleasant features took on a constipated grimace and he snarled, ‘Peabody, you vile excuse for a policeman, when did you get here?’

Alf replied that we had only just arrived. At which point our helpful poacher came onto the scene, returned from his vigil at the telephone box. He said nothing, the presence of so many blue uniforms suddenly making him worry that he was going to be blamed for something. Even his dog, sensing the tension, refrained from revisiting the ripe pleasures of Alf’s crotch.

Bristling and menacing, all silver braid and bossiness, Inspector Stanley said, “A call came into our control room nearly two hours ago about a body in the river. It’s taken us an age to find the bloody thing and what do I see but you, hanging around like a bad smell.’

Not nice, I thought, but knowing the ways of my partner I guessed their paths had crossed before and this inspector had come off worse.

Alf adopted a pained expression and replied, ‘We were just driving by and this good gentleman flagged us down. We made our observations, governor, and were about to radio in to request that your force be notified. After all, it is on Suffolk’s side and I knows just how serious you takes territorial issues.’

The inspector then turned his basilisk stare at our ‘good gentleman’, who looked as if he was going to pee himself. ‘I know you,’ he said. ‘What are you doing, poaching again?’

Alf quickly interjected, ‘No, governor, this man has been helping us. He came across the deceased whilst walking his dog and phoned nine-nine-nine, then waited at the phone box till someone turned up. Must have been waiting an age. Could have buggered off but he didn’t, which was good of him. Otherwise we’d never have found the place at all.’

That was received by our shiny inspector with sneer of disbelief and the two poor sods with him looked seriously unchuffed at the prospect of a bit of corpse fishing. Looks that wished they could kill, or at least permanently maim, were directed at Alf and me that morning.

Alf then announced that, as we were no longer needed at the scene, we would check our side of the A604 for any sign as to why or where the deceased might have entered the river. There were at least three road bridges across the Colne on the Essex side and, after checking them, we would submit a report to our HQ for them to pass on to Suffolk.

There was nothing the inspector could say. He knew it, and the coppers with him knew it. My only remaining concerns were our witness and, of course, our broom, which, although thrown into the undergrowth, might yet be found.

Alf, oozing co-operative zeal then asked if it would help if we ‘copped a statement’ off the witness and forwarded that along with the report of our bridge investigations.

A brief nod accompanied a ‘fuck off’ gesture from old bum-face and we hurried our ‘witness’ up the lane. Sitting him down until we all got our timing right, we took a very brief statement from him. Finally, with his old dog giving one last loving sniff at Alf’s trousers, he gratefully departed. For him it had been a long morning and not without incident.

For us it was the start of a drive up and down the highway looking for ‘clues’.

There were none. From down river, the village of Baythorne End had a bridge over the Colne but it was intact, with brick walls either side. Going up river as far as Haverhill in Suffolk, although the road roughly followed the Colne, there were no bridges directly over it. There was, however, a bridge over the Colne Brook near the village of Sturmer, not far ‘as the body floats’ from where our cyclist eventually ended up.

The bridge itself was intact, but a low fence that went right up to the parapet was broken. This bridge was narrow, just two car widths wide, and had no footpath. The fence was close by a passing area on the right-hand side going towards a junction on the main A604. This passing area was called ‘Water Lane’, which says it all.

Our conclusion—and not being present at the inquest we never knew the ‘official’ line—was that the bicyclist somehow got lost and found himself riding down this lane towards the main road. The weather had been lousy over the previous few days, with torrential rain. So maybe the poor sod was wet and tired, and a wee bit lost. Perhaps he was startled by an on-coming vehicle, headlights blazing no doubt, and veered to his right and straight into the brook.

We’ll never know.

What we do know is that he was Dutch, aged 23, a student studying at Cambridge who had planed to cycle home on the previous Friday night. Which, evidently, he had done twice before. He had on him his passport and ferry ticket, and two panniers on the rear of the bike filled with clothes. No wonder that was the heaviest bit!

I’m just so glad I didn’t have the horror of being there when his parents identified the body. Trust me, that really is a shit job.

For the Floating Dutchman, his journey was ended. For me, I had a few more years in that bloody uniform and some more adventures along the way. If you’re all good, and like the idea, I’ll write some more—perhaps.

Mind how you go.

Great story, Bernard. I hope there are many more of them.

LikeLike

I’m so glad you liked it. This is a new departure for me so I’m just a tad nervous. And yes. lots more stories to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

you must put all your stories in a book and have it published I would be the first to buy it but not the last

LikeLike

Oh Di – you’re only saying that because your rugby team gave us such a good spanking and you’re being nice…

LikeLike

Truly enjoyable, thank you. Look forward to reading more, please.

LikeLike

It’s good see one of your stories in print – it’s a right racy read! Keep ’em coming please!

LikeLike

Very funny story, Bernard – but made all the funnier by the way you tell it! I can just hear your lovely voice as you relate this tale – please tell us the one about your gardening exploits in the police house!

LikeLike

Yep …….

It shall be told, sort of!

Thank you for your support

LikeLike

I do love your stories and your way of telling them. The one about the grenade that you told at the con had me in stitches. More, more!

LikeLike

Hells bells, B. This is seriously good. Definitely carries your voice (a good thing). Your imagery, and the line you tread between humour and dark pathos are magic. More, please! X

LikeLike

I’m loving your stories and thoroughly enjoyed the ones you told at IDWCON in Cork in October. Please come back and tell us more

LikeLike