When I was first a village copper there were few street lights. The big house in the square had a rather grand lantern mounted in wrought iron above the gate and the dim light somehow darkened rather than illuminated the doorway. Lights from house windows cast a welcome glow onto the pavement until midnight or thereabouts but were slowly extinguished as the residents took to their beds or other nocturnal pursuits.

When I was first a village copper there were few street lights. The big house in the square had a rather grand lantern mounted in wrought iron above the gate and the dim light somehow darkened rather than illuminated the doorway. Lights from house windows cast a welcome glow onto the pavement until midnight or thereabouts but were slowly extinguished as the residents took to their beds or other nocturnal pursuits.

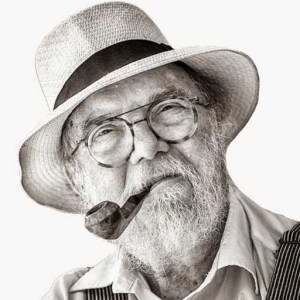

Then the night was mine, my time to walk my village. I walked my beat, clad in dark regulation uniform, smoking my pipe and moving silently in rubber-soled boots, a bloody great torch in my pocket. I shook hands with the doorknobs to make sure people were safe and property was secure. I protected my villagers from thieves and villains and I would have defended them from attack with my life if it had come to it. I did my duty, this was my job. Far more important to me than nicking some poor sod without road fund license or feeling the collar of a bloke after he’d put a rabbit or even a pheasant in his cooking pot, keeping the peace, keeping them safe.

Constable is an old title, it used to be watchman and before that there was the lookout, the man designated to guard the settlement and keep the sovereign’s peace.

Strange things go on in English villages at night. Many strange things and some of them involve the dead as well as the living. I don’t mean murder or mayhem or the planting of bodies under a rose bed, though that does happen. Rather, I mean the aura of a place that has known the footfall of mankind for centuries. When the paths that you walk lead to the ancient homes of countless generations, then the night sometimes belongs more to them than you. On my beat I walk slowly and quietly. I know where to stand protected from the wind and the rain and I know where the shadows cloak me so I can see all around without being seen. And sometimes, all of a sudden, the past will move a mite closer, the centuries will roll back and the echo of forgotten sounds and voices will whisper in the silence.

It wasn’t a big village, we had a castle mind, a proper one with battlements and its Norman keep still standing. The church was in the centre and the streets had been laid out around the old market square when the castle was still stones on the hod-carrier’s shoulders. There was a mixture of large houses and small; some dilapidated through neglect and some well-cared for with fresh paint and polished brass. There were a few shops and a couple of pubs and that was it really.

But there was a place that always caught my attention. It was a small space by the entrance to the church yard and it was somehow in shadow on even the sunniest day. I have watched the great and the good spill from the church on Sunday mornings and congratulate themselves on having survived another of the Reverend Hammond’s ‘borathons’, and even when the crowd extended into the street and along the wall by press of bodies and cars, that small place was somehow missed, almost shunned.

I never thought too much of it normally but one day, lurking in ‘Benny the Palms’  second hand bookshop and clairvoyant clinic, I came across a history of local martyrs. An unusual thing to write about and a bloody history lesson in every sense of the word. The bit that caught my eye was a brief mention of a local scholar who had been burned as a heretic. This young man had refused to bow to the wishes of his elders and betters and had paid for it with his life. The dreadful deed had taken place some way hence in our county town but it did say he was a man of the village and that his father having the living here as parish priest lived on for some time afterwards in ‘great sorrow and distress’.

second hand bookshop and clairvoyant clinic, I came across a history of local martyrs. An unusual thing to write about and a bloody history lesson in every sense of the word. The bit that caught my eye was a brief mention of a local scholar who had been burned as a heretic. This young man had refused to bow to the wishes of his elders and betters and had paid for it with his life. The dreadful deed had taken place some way hence in our county town but it did say he was a man of the village and that his father having the living here as parish priest lived on for some time afterwards in ‘great sorrow and distress’.

Ben ran his dilapidated second-hand bookshop as a library for his friends and, in addition to his clairvoyant and palm-reading activities which drew a wide clientèle; he was also a respected local historian. He suggested I make a visit to the county library and maybe look at church records.

There is something in the psyche of some of us coppers that is a mixture of pure nosiness, the desire to turn over the stones of life and examine what is beneath them, and a belief in natural justice and old-fashioned fair play.

A sixth sense develops from experiencing the human condition at its best and worst and sometimes the little aberrations and foibles of human nature suggest something is not right, not what it seems. This little tale, barely a footnote, resonated in my head. A young man, burned as a warning, a father whose grief was still palpable after several centuries and a growing awareness that there was more to discover and the story was unfinished.

I was therefore off to the county library the next day, delving about in the archive and chatting up the clever sods that lurked in amongst the shelves. I had precious little to go on – a name, a date and the times they lived in. It seemed that the young clerk in holy orders, as he turned out to be, was a scholar of Jesus College Cambridge and a very bright lad too. I imagined him full of confidence, just graduated, his first job, a bit of preferment perhaps from his father’s patron. Then falling foul of the establishment, making waves, being a bloody nuisance until someone decided that the threat of torching might bring him to heel. What was his old dad doing, wringing his hands and moving heaven and earth to bring the lad out of the firing-line.

Who knows?

But eventually someone like me was told to hold, guard and keep him and deliver him safe to the place of his execution. Some poor bloody copper had a crap job and a young man was burned to death.

The church records shed little more light except that the father was not recorded as parish priest for long after his son’s death. But then Benny found me an old 19th century plan of the village and on it was marked the place where some dissenters had been interred. Things began to fall into place. My bit of ‘spooky’ church wall was just outside the boundary of the original grave-yard. It was near this space that the suicides and the un-baptised were buried.

And perhaps also buried here were the remains of a young man whose ideas and visions led to his untimely death. Benny had said that the policy of the day was that the small residue of death by burning was crushed beyond recognition and scattered to the four winds ‘that their infamy may ever again be visited upon the world’ so it was writ. But I had a hunch that this was not always so. Some copper had to guard that smouldering pyre, some copper might well have seen an old man, in such pain as made the soul wither, and who had come to see his son die. To wait the long night, thinking of the child that grew, that questioned and quested and died because of it. Some copper might well have been a father also, and turned away, for a moment.

So perhaps, just perhaps, an old priest lay to rest some remnant of his child beneath a wall, close to the church, but never part of it. Perhaps that shade spoke across the years to another upholder of the law. I will never know. But I did place a small bunch of forget-me-nots on that spot. On the curtailment of the old churchyard, and I never did feel the quiet unease again. Nor do I think that it’s there even now.

Oh, I do like this story, Bernard Pearson. Well told, sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Bernard. Beautifully told.

LikeLike

Bless you Nancy, from a storyteller such as yourself, a true accolade. Thank you.

LikeLike

A way with words he has…

LikeLike

Except for the rubber-soled boots I could picture Sam Vimes.

LikeLike

Properly told by a proper story teller, thank you

LikeLike

Lovely tale, nicely told x

LikeLike

wonderful story Bernard, it is strange how some places have vibes all of their own.

LikeLike

I can hear your voice reading to me a bedtime story thank you Bernard xx

LikeLike

A beautiful story, Bernard. Thank you.

LikeLike

Beautifully told sir.

Yet again

See you before I need to.use my 2016 diary 🙂

LikeLike

What a thoughtful story. I enjoyed it. You are a natural storyteller, Sir. Thank you

LikeLike

Very nice story Bernard thoroughly enjoyed it.

LikeLike

It brought several tears to my eyes and as I’m sat in the pub waiting for my friends I’m getting some very odd looks….

LikeLike